Los “relojes” de los cuásares muestran que el universo era 5 veces más lento justo después del Big Bang

En un estudio pionero, los científicos utilizaron cuásares como relojes cósmicos para observar el universo primitivo en cámara extremadamente lenta, validando aún más la teoría de la relatividad general de Einstein. Al examinar los datos de casi 200 cuásares, agujeros negros supermasivos hiperactivos en los centros de las primeras galaxias, el equipo descubrió que el tiempo parecía fluir cinco veces más lento cuando el universo tenía poco más de mil millones de años.

Los datos de observación de casi 200 cuásares muestran que Einstein tiene razón, nuevamente, sobre la dilatación del tiempo en el cosmos.

Los científicos han observado el universo primitivo funcionando en cámara extremadamente lenta por primera vez, desbloqueando uno de los misterios de Einstein sobre el universo en expansión.

La teoría general de la relatividad de Einstein significa que deberíamos observar el universo distante, y por lo tanto antiguo, funcionando mucho más lentamente de lo que lo hace hoy. Sin embargo, mirar hacia atrás en el tiempo resultó difícil de alcanzar. Los científicos ahora han desentrañado este misterio usando cuásares como ‘relojes’.

“Mirando hacia atrás a una época en la que el universo tenía poco más de mil millones de años, vemos que el tiempo parece fluir cinco veces más lento”, dijo el autor principal del estudio, el profesor Geraint Lewis, de la Escuela de Física y el Instituto de Astronomía de Sydney, en el Universidad de Sídney.

“Si estuvieras allí, en este universo infantil, un segundo parecería un segundo, pero desde nuestra posición, más de 12 mil millones de años en el futuro, ese tiempo inicial parece demorarse”.

La investigación fue publicada el 3 de julio en Astronomía de la Naturaleza.

Profesor Geraint Lewis del Instituto de Astronomía de Sydney en la Escuela de Física de la Universidad de Sydney. Crédito: Universidad de Sydney

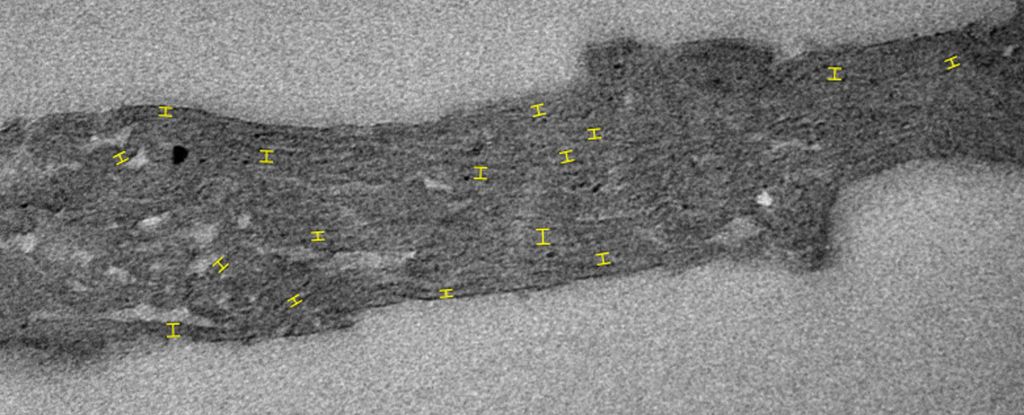

El profesor Lewis y su colaborador, el Dr. Brendon Brewer, de la Universidad de Auckland, utilizó datos observados de casi 200 cuásares (agujeros negros supermasivos hiperactivos en el centro de las primeras galaxias) para analizar esta dilatación del tiempo.

“Gracias a Einstein, sabemos que el tiempo y el espacio están entrelazados, y desde el comienzo de los tiempos en la singularidad del Big Bang, el universo se ha estado expandiendo”, dijo el profesor Lewis.

“Esta expansión del espacio significa que nuestras observaciones del universo primitivo deben parecer mucho más lentas que el flujo del tiempo actual.

“En este documento, establecimos que se remonta a unos mil millones de años después de la[{” attribute=””>Big Bang.”

Previously, astronomers have confirmed this slow-motion universe back to about half the age of the universe using supernovae – massive exploding stars – as ‘standard clocks’. But while supernovae are exceedingly bright, they are difficult to observe at the immense distances needed to peer into the early universe.

By observing quasars, this time horizon has been rolled back to just a tenth the age of the universe, confirming that the universe appears to speed up as it ages.

Professor Lewis said: “Where supernovae act like a single flash of light, making them easier to study, quasars are more complex, like an ongoing firework display.

“What we have done is unravel this firework display, showing that quasars, too, can be used as standard markers of time for the early universe.”

Professor Lewis worked with astro-statistician Dr. Brewer to examine details of 190 quasars observed over two decades. Combining the observations taken at different colors (or wavelengths) – green light, red light, and into the infrared – they were able to standardize the ‘ticking’ of each quasar. Through the application of Bayesian analysis, they found the expansion of the universe imprinted on each quasar’s ticking.

“With these exquisite data, we were able to chart the tick of the quasar clocks, revealing the influence of expanding space,” Professor Lewis said.

These results further confirm Einstein’s picture of an expanding universe but contrast earlier studies that had failed to identify the time dilation of distant quasars.

“These earlier studies led people to question whether quasars are truly cosmological objects, or even if the idea of expanding space is correct,” Professor Lewis said.

“With these new data and analysis, however, we’ve been able to find the elusive tick of the quasars and they behave just as Einstein’s relativity predicts,” he said.

Reference: “Detection of the cosmological time dilation of high-redshift quasars” by Geraint F. Lewis and Brendon J. Brewer, 3 July 2023, Nature Astronomy.

DOI: 10.1038/s41550-023-02029-2

“Creador malvado. Estudiante. Jugador apasionado. Nerd incondicional de las redes sociales. Adicto a la música”.