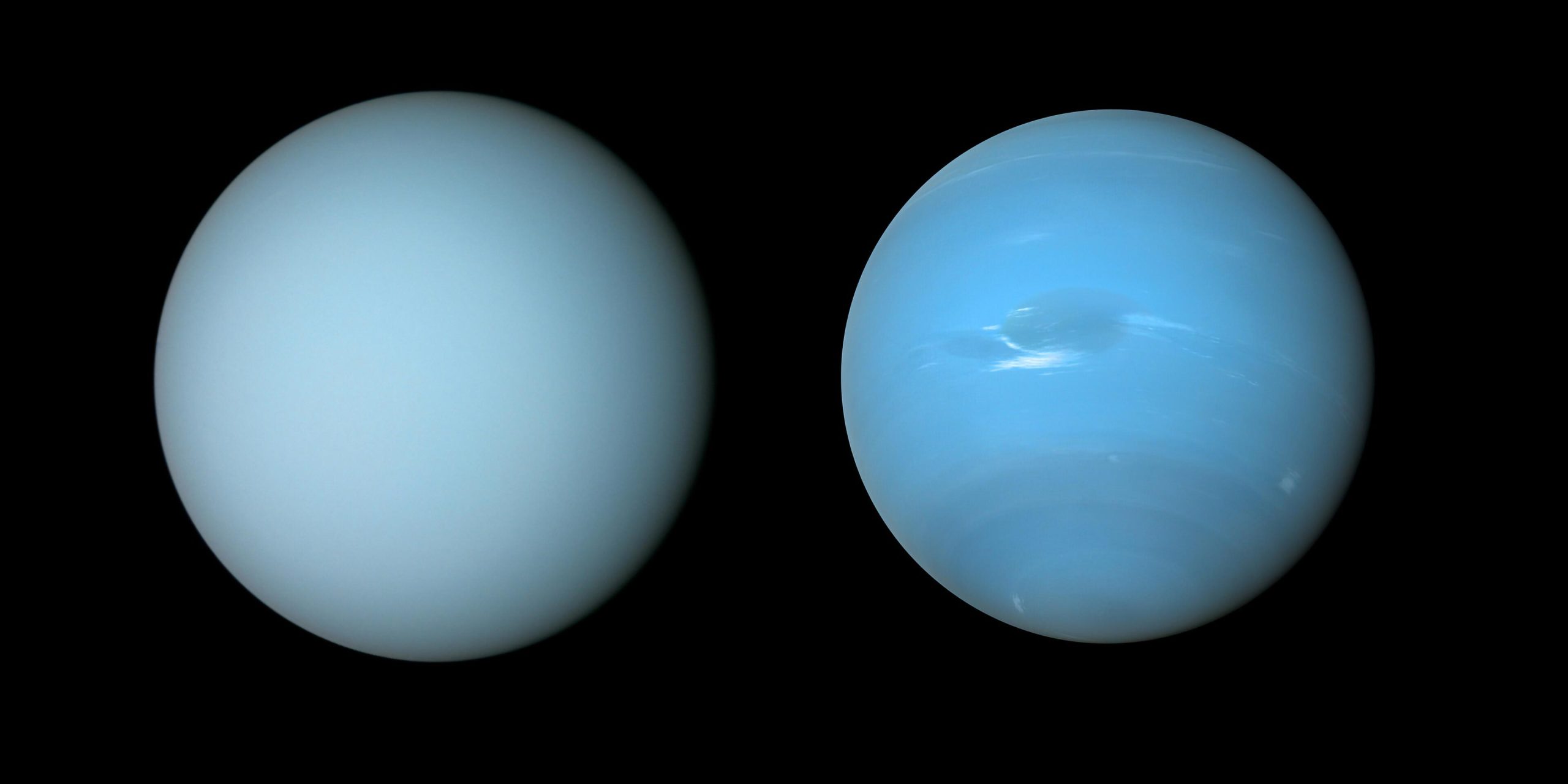

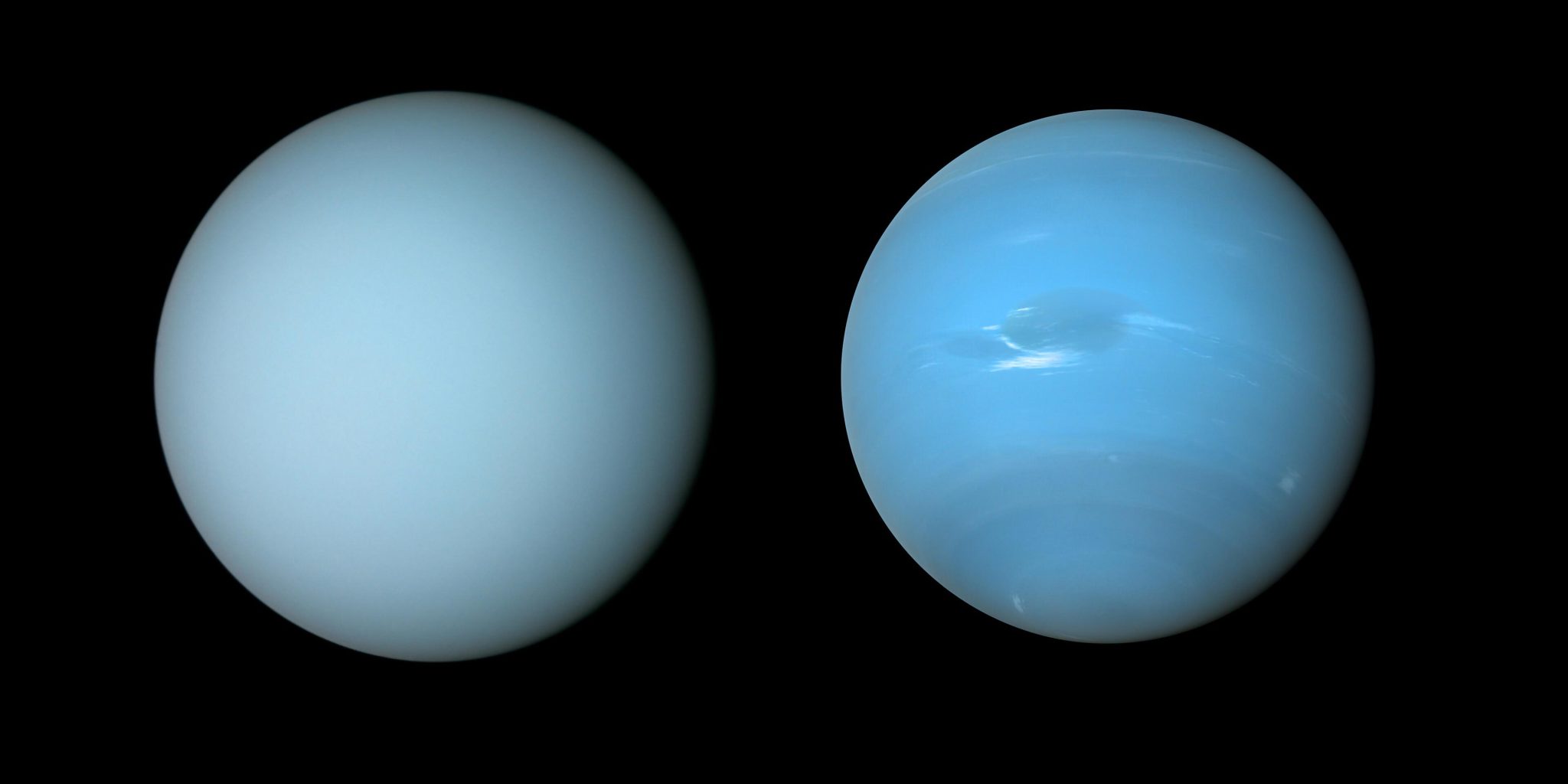

La nave espacial Voyager 2 de la NASA capturó estas vistas de Urano (izquierda) y Neptuno (derecha) durante sus sobrevuelos de los planetas en la década de 1980. Crédito: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Jonsson

Las observaciones del Observatorio Gemini y otros telescopios revelan que el exceso de neblina[{” attribute=””>Uranus makes it paler than Neptune.

Astronomers may now understand why the similar planets Uranus and Neptune have distinctive hues. Researchers constructed a single atmospheric model that matches observations of both planets using observations from the Gemini North telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, and the Hubble Space Telescope. The model reveals that excess haze on Uranus accumulates in the planet’s stagnant, sluggish atmosphere, giving it a lighter hue than Neptune.

Los planetas Neptuno y Urano tienen mucho en común: tienen masas, tamaños y composiciones atmosféricas similares, pero su apariencia es notablemente diferente. En longitudes de onda visibles, Neptuno tiene un color claramente más azul, mientras que Urano tiene un tono pálido de cian. Los astrónomos ahora tienen una explicación de por qué los dos planetas son de diferentes colores.

Una nueva investigación sugiere que una capa de neblina concentrada que existe en ambos planetas es más gruesa en Urano que una capa similar en Neptuno y “blanquea” la apariencia de Urano más que la de Neptuno.[1] Si no hubiera niebla en el atmósferas de Neptuno y Urano, ambos aparecerían casi igualmente azules.[2]

Esta conclusión proviene de un modelo[3] que un equipo internacional dirigido por Patrick Irwin, profesor de Física Planetaria en la Universidad de Oxford, desarrolló para describir capas de aerosoles en las atmósferas de Neptuno y Urano.[4] Investigaciones previas de las atmósferas superiores de estos planetas se han centrado en la apariencia de la atmósfera solo en longitudes de onda específicas. Sin embargo, este nuevo modelo, que consta de múltiples capas atmosféricas, corresponde a observaciones de ambos planetas en un amplio rango de longitudes de onda. El nuevo modelo también incluye partículas de neblina dentro de capas más profundas que anteriormente se pensaba que contenían solo nubes de hielo de metano y sulfuro de hidrógeno.

Este diagrama muestra tres capas de aerosoles en las atmósferas de Urano y Neptuno, modeladas por un equipo de científicos dirigido por Patrick Irwin. La escala de altura del diagrama representa una presión superior a 10 bar.

La capa más profunda (la capa Aerosol-1) es gruesa y está compuesta por una mezcla de hielo de sulfuro de hidrógeno y partículas producidas por la interacción de las atmósferas de los planetas con la luz solar.

La capa clave que afecta los colores es la capa intermedia, que es una capa de partículas de neblina (referida en el artículo como la capa Aerosol-2) que es más gruesa en Urano que en Neptuno. El equipo sospecha que en ambos planetas, el hielo de metano se condensa sobre las partículas de esta capa, arrastrando las partículas más profundamente hacia la atmósfera en una lluvia de nieve de metano. Como Neptuno tiene una atmósfera más activa y turbulenta que Urano, el equipo cree que la atmósfera de Neptuno es más eficiente para remover partículas de metano en la capa de neblina y producir esta nieve. Esto elimina más neblina y mantiene la capa de neblina de Neptuno más delgada que en Urano, lo que significa que el color azul de Neptuno parece más fuerte.

Por encima de ambas capas hay una capa extendida de niebla (la capa de Aerosol-3) similar a la capa de abajo, pero más tenue. En Neptuno, también se forman grandes partículas de hielo de metano por encima de esta capa.

Crédito: Observatorio Internacional Gemini/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, J. da Silva/NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Jonsson

“Este es el primer modelo que ajusta simultáneamente las observaciones de la luz solar reflejada desde el ultravioleta hasta el infrarrojo cercano”, explicó Irwin, autor principal de un artículo que presenta este resultado en el Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. “También es el primero en explicar la diferencia de color visible entre Urano y Neptuno”.

El modelo del equipo consta de tres capas de aerosoles a diferentes alturas.[5] La capa principal que afecta a los colores es la capa intermedia, que es una capa de partículas de niebla (denominada en el artículo capa de Aerosol-2) que es más gruesa. Urano que en Neptuno. El equipo sospecha que en ambos planetas, el hielo de metano se condensa sobre las partículas de esta capa, arrastrando las partículas más profundamente hacia la atmósfera en una lluvia de nieve de metano. Como Neptuno tiene una atmósfera más activa y turbulenta que Urano, el equipo cree que la atmósfera de Neptuno es más eficiente para remover partículas de metano en la capa de neblina y producir esta nieve. Esto elimina más neblina y mantiene la capa de neblina de Neptuno más delgada que en Urano, lo que significa que el color azul de Neptuno parece más fuerte.

“Esperábamos que el desarrollo de este modelo nos ayudara a comprender las nubes y la neblina en las atmósferas de hielo gigante”, dijo Mike Wong, astrónomo del[{” attribute=””>University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the team behind this result. “Explaining the difference in color between Uranus and Neptune was an unexpected bonus!”

To create this model, Irwin’s team analyzed a set of observations of the planets encompassing ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths (from 0.3 to 2.5 micrometers) taken with the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) on the Gemini North telescope near the summit of Maunakea in Hawai‘i — which is part of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab — as well as archival data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, also located in Hawai‘i, and the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

The NIFS instrument on Gemini North was particularly important to this result as it is able to provide spectra — measurements of how bright an object is at different wavelengths — for every point in its field of view. This provided the team with detailed measurements of how reflective both planets’ atmospheres are across both the full disk of the planet and across a range of near-infrared wavelengths.

“The Gemini observatories continue to deliver new insights into the nature of our planetary neighbors,” said Martin Still, Gemini Program Officer at the National Science Foundation. “In this experiment, Gemini North provided a component within a suite of ground- and space-based facilities critical to the detection and characterization of atmospheric hazes.”

The model also helps explain the dark spots that are occasionally visible on Neptune and less commonly detected on Uranus. While astronomers were already aware of the presence of dark spots in the atmospheres of both planets, they didn’t know which aerosol layer was causing these dark spots or why the aerosols at those layers were less reflective. The team’s research sheds light on these questions by showing that a darkening of the deepest layer of their model would produce dark spots similar to those seen on Neptune and perhaps Uranus.

Notes

- This whitening effect is similar to how clouds in exoplanet atmospheres dull or ‘flatten’ features in the spectra of exoplanets.

- The red colors of the sunlight scattered from the haze and air molecules are more absorbed by methane molecules in the atmosphere of the planets. This process — referred to as Rayleigh scattering — is what makes skies blue here on Earth (though in Earth’s atmosphere sunlight is mostly scattered by nitrogen molecules rather than hydrogen molecules). Rayleigh scattering occurs predominantly at shorter, bluer wavelengths.

- An aerosol is a suspension of fine droplets or particles in a gas. Common examples on Earth include mist, soot, smoke, and fog. On Neptune and Uranus, particles produced by sunlight interacting with elements in the atmosphere (photochemical reactions) are responsible for aerosol hazes in these planets’ atmospheres.

- A scientific model is a computational tool used by scientists to test predictions about a phenomena that would be impossible to do in the real world.

- The deepest layer (referred to in the paper as the Aerosol-1 layer) is thick and is composed of a mixture of hydrogen sulfide ice and particles produced by the interaction of the planets’ atmospheres with sunlight. The top layer is an extended layer of haze (the Aerosol-3 layer) similar to the middle layer but more tenuous. On Neptune, large methane ice particles also form above this layer.

More information

This research was presented in the paper “Hazy blue worlds: A holistic aerosol model for Uranus and Neptune, including Dark Spots” to appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

The team is composed of P.G.J. Irwin (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), N.A. Teanby (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK), L.N. Fletcher (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), D. Toledo (Instituto Nacional de Tecnica Aeroespacial, Spain), G.S. Orton (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA), M.H. Wong (Center for Integrative Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, USA), M.T. Roman (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), S. Perez-Hoyos (University of the Basque Country, Spain), A. James (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), J. Dobinson (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK).

NSF’s NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), the US center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the international Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and Vera C. Rubin Observatory (operated in cooperation with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. The astronomical community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that these sites have for the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Native Hawaiian community, and the local communities in Chile, respectively.

“Creador malvado. Estudiante. Jugador apasionado. Nerd incondicional de las redes sociales. Adicto a la música”.